What Will the Full Impact be?

Economic data can only ever paint a portrait of the past. The recent past, to be sure, but the past nonetheless. The monthly value of printing shipments data we regularly present are two months old by the time it is reported (the numbers presented in the sidebar to this article were released in March and include data up through January). The profits data are even less timely; they are only reported quarterly and thus the numbers are only through Q4 2019.

This type of data lag is not usually a problem, as we are more interested in long-term trends than in what happened yesterday. We do eagerly await the monthly shipments data and cheer when a month is up, or boo when a month is down, but what’s more important is what is happening in the long run. Monthly, and especially weekly, data can be somewhat “noisy”; there can be things that make a particular data series tick up or down, which will probably not be a factor the following month: unseasonably bad weather in one February, unseasonably good weather in another, a hurricane in one June, a major election in one November or perhaps even a pandemic.

The Month the Universe Changed

In March 2020, or February in some countries, the world turned upside-down.

The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the economy was so swift and intense that presenting any chart of pre-March data will be the equivalent of printing pictures of puppies—calming, consoling and heartwarming.

As we write this in early April, we have no clear sense of what the ultimate impact will be on the economy, or on the printing industry, other than a general “not good” (although we will speculate below). In mid-March, we launched a quick survey to get a sense of what the expected impact will be on the printing industry, and while all precincts haven’t yet reported in, two-thirds of respondents thus far are expecting 2020 revenues to be down more than 10% from 2019, and 70% expect jobs/orders to be down more than 10%. More than half have put whatever hiring plans they had on hold (around 40% are downsizing their production staff) and around 40% are putting whatever investment plans they had on hold—although, to be fair, not many print businesses had any major investment plans for 2020, as we found in our fall 2019 survey.

In terms of industry data, we won’t know the full impact of the health crisis until the summer. March shipments will be released in May, and while we expect the data to be bad, the badness will probably be somewhat tempered, since the month started out OK. We’ll get April shipments data in early June, and that’s when we can expect to see some trend lines plummet through the x-axis and maybe through the floor. Sorry to say, but that’s the expectation.

Even regular macroeconomic data are lagging reality. On April 3, the March employment figures were released, and the headline unemployment rate increased to 4.4%, up from 3.6% in February, and March job loss was 701,000. The Bureau of Labor Statistics noted some problems with the March survey (see their FAQ at https://bit.ly/39HGDnf) and it’s possible that the unemployment rate is as high as 5.5%. That’s a big jump, but economists are expecting that to be dwarfed by next month’s report, which we’ll probably see just as this issue is hitting mailboxes. (Another reporting problem is the lag time between when we have to submit this article and when you get it in the mail. If we were off by a million miles and everything is fine when you get this, consider this our “Dewey Defeats Truman” moment. We’d be thrilled about that, actually.)

One data series that has been more timely in tracking the fallout from the crisis is weekly initial unemployment claims. On March 27, the Department of Labor announced that weekly unemployment claims surged from the previous week’s 282,000 to 3.28 million. That was the highest number of initial jobless claims since 1967, when the DOL started tracking them. The previous record high was a “mere” 695,000 back in October 1982. Then, on April 2, weekly unemployment claims doubled to 6,648,000, and the scary thing is that number probably undercounts the unemployed, as it doesn’t include freelancers, gig workers, or other members of the 1099 club who don’t qualify for unemployment. (Although the CARES Act changes this; see below.) In our industry, this mostly impacts freelance writers, designers, illustrators and other creatives. Can we make a wild-ass guess that if the weekly claim data doubled in April that the overall unemployment rate has at least doubled? Expectations were that we would be at 20% soon.

Source: Department of Labor. Shaded areas indicate recessions.

Essential Businesses

One major impact the crisis has had on the printing industry is in the case of closing “nonessential businesses.” Whether a business is essential or not is determined at the state level, and in some states, printing is not considered an essential business, and thus printing companies are not allowed to remain open. In some states, printers—particularly those that produce signage—have been considered essential because they serve hospitals and other medical centers. Some print businesses opted to close anyway, even if they were allowed to remain open, out of safety concerns.

Even when print businesses have been allowed to remain open, they have been seeing a decline in work. As our survey respondents indicated, they are seeing and expecting declines in jobs and ultimately revenues. On the plus side, a number of print businesses have been doing pro bono work for their communities, making masks and other personal protection equipment (PPE). This much-needed assistance may not bring in immediate revenue, but it is good PR and may yield new business once things return to normal (someday.)

We know that upcoming industry and macroeconomic indicators are going to be bad, and you know better than anyone how your own business and local economy are faring. The real questions, for which these data series are no help, are: how long is this health crisis likely to last, and what will be the long-term impact?

How Long Must This Go On?

First and most pressing is, when will the country be open for business again? Unfortunately, no one really knows.

People who have been following the pandemic use Italy as a benchmark, where the disease hit the earliest (in terms of Western countries) and most aggressively. As of April 3, Italy’s crisis seems to have peaked, but other European countries, and the U.S., have yet to come close to peaking, which may not happen until mid-May, if everyone follows the Italy timeline—which not everyone is. (The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation [IHME] reports pandemic peak projections by state at healthdata.org.)

The best-case scenario is that the disease peaks in mid-May, ebbs by the middle of June, and we can return to some semblance of normal by August. If it is that short-lived (and if that doesn’t sound “short-lived” just remember how g------n long March felt, there might not be much lasting impact at all—if the CARES Act does what it was supposed to do. (That is a big “if.”)

There is a historical precedent we need to bear in mind, and that is the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, one aspect of which is often forgotten: it came in two waves. The first wave in early 1918 was virulent, but not appreciably worse than a normal flu. So when new cases waned as the weather warmed, everyone let down their guard. Then the virus mutated, and the second wave, which hit in fall 1918, was the deadly one. The death toll is estimated to have been anywhere from 17 to 50 million—and possibly as high as 100 million. The key to keeping it from being even worse was quarantining. Cities that instituted lockdowns early in the crisis had fewer deaths than cities that instituted them later. And evidence from the current pandemic strongly suggests that the self-quarantining and social distancing are actually working. As frustrating, maddening and boring as it has been, the alternative is far worse. What is not yet clear from the health data is whether we are likely to face some level of social distancing again later in the year if it pulls a 1918 on us.

Ultimate Economic Impact

What the long-term effects of the COVID-19 crisis will be are also unknown—and in large part unknowable. On March 31, Goldman Sachs weighed in with their forecast.

Goldman Sachs said the second-quarter U.S. economic decline would be much greater than it had previously forecast and unemployment would be higher, citing anecdotal evidence and "sky-high jobless claims numbers" resulting from the coronavirus pandemic.

Goldman is now forecasting a real GDP sequential decline of 34% for the second quarter on an annualized basis, compared with its earlier estimate for a drop of 24%. It also cut its first-quarter target to a decline of 9% from its previous expectation for a 6% drop, according to chief economist Jan Hatzius.

The firm now sees the unemployment rate rising to 15% by mid-year compared with its previous expectation for 9%.

Unlike past economic crises which triggered massive reductions in demand, for the most part, demand is still high. People have money, they just can’t spend it anywhere, except, apparently, on toilet paper. No one is going out to eat, no one is going out to bars, or to the gym, or getting their hair cut. No one is buying a car or other major items. And few people are having things printed. (CDC and other safety signage, as well as labels and packaging for in-home delivery, have been the exceptions.) Once the lockdown is over, there will be a massive surge of pent-up demand. We know more than a few people—like us—who are planning “major happy hour outings” when this is over. Business travel will bounce back as all—or at least some—of the events that were cancelled or postponed take place. (Leisure travel will take longer to recover, particularly cruises.) There will be a spate of home improvement projects to repair the damage caused by the kids being home 24/7. Retail stores with seasonal inventory will take a hit, but those that benefited from quarantined shopaholics’ e-commerce sales will come back more quickly. (This is all dependent on it being a short-lived health crisis, and the government assistance actually working. Another big if.)

For people still receiving a paycheck, this has been a good time to save and when they are allowed out again, that will probably be the biggest economic stimulus.

But—not everyone is receiving a paycheck. As businesses have had to close, many have had little choice but to lay off or furlough their staff—and the initial unemployment claims numbers give us an idea of the number of these folks. These recently unemployed can cope with not going out to restaurants, but they do have other bills—rent/mortgage, car payments, utilities, and of course food. Without some kind of assistance, these people are going to have a hard time making it to August, let alone splurging when it’s over. This is all without even mentioning any medical expenses that may be incurred as a result of contracting the virus. This is why the cash payments included in the CARES Act were so important, although for many it will not be enough, especially if the crisis lasts beyond the summer. As of early April, there have been some snafus, and physical checks, for those who do not have direct deposit set up with the IRS, will be mailed at a later date and may not arrive until too late. An important part of the legislation—and, let’s be honest, it should be thought of as disaster relief, not economic stimulus—is that it allows freelancers and gig workers to apply for unemployment. It also expands unemployment benefits.

Helping individuals get through the crisis was (or should have been) one of the two biggest priorities of any governmental response to the COVID-19 crisis, as it will allow them to pay their essential bills until they are able to go back to their jobs.

The second big priority is helping businesses, especially small businesses, survive so that those employees have jobs to go back to. Restaurants, bars or any other closed businesses (like printers) have no customers and are receiving no income—and they, too, have bills to pay. So the CARES Act also includes loans to small businesses. Said Forbes:

[The] Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) of the CARES Act increases the government guarantee of loans to 100 percent through Dec. 31, 2020, for SBA 7(a) loans. The loans are available to companies with not more than 500 employees and those which have below a gross annual receipts threshold in certain industries. Under the legislation, 501(c)(3) nonprofits, sole-proprietors, independent contractors, and other self-employed individuals are eligible for loans.

A complete explanation of the CARES Act is beyond the scope of this article. For more information see the Senate Committee on Small Business & Entrepreneurship guide to the CARES Act at https://bit.ly/3aHawW8.

When the PPP was launched in early April, there were some problems, which hopefully have been resolved by May.

The keys to the best-case scenario happening are:

- The CARES Act keeps individuals and businesses afloat until the crisis passes. (A big “if.”)

- Or, if more relief turns out to be necessary, the government acts in a timely manner to address the problem. (Yeah, you probably did a spit-take there.)

- And, we don’t jump the gun, attempt to return to normal too soon, and thus trigger a second wave à la 1918. Quarantining is working.

- On the other hand, we can’t get so fearful that once the threat does appear to have passed, we keep quarantining and refrain from economic activity.

- A treatment becomes readily—and affordably—available. A vaccine is not likely to be available in less than a year, even though a potential vaccine is about to go into clinical trials. What is more likely is that something mitigates the symptoms of the disease. At present, nothing has been conclusively proven to treat COVID-19 symptoms, despite anecdotal evidence to the contrary.

- We listen to actual medical and science experts.

Striking the balance between three and four is the tricky part, and six would be a nice change from science à la Twitter.

We are in for a rough ride, but we as an industry are used to rough rides. We’ll ride out the bucking economy (that’s bucking with a b), but we just might be walking funny for a while.

Pictures of Puppies

“Of all sad words of tongue or pen, the saddest are these, ‘It might have been.’” —John Greenleaf Whittier

This is a printing industry trade magazine, not a medical journal, so we will carry on with our industry analysis subject to the many caveats above. These are pre-March charts, so they’re best looked at through the lens of nostalgia, or perhaps the calm before the storm. Still, they do have some lessons to teach us.

Shipments

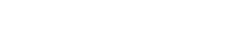

After having the best year in half a decade, we began 2020 on a high note: January shipments came in at $6.94 billion, and while that was down from December’s $6.98 billion, it was just slightly lower than January 2016’s $6.95 billion—making January 2020 the best January we have had since then. Sigh.

If there is a silver lining to all of this, it’s that we as an industry went into this crisis in the best shape we have been in in a long time. If this had happened even a few years earlier, we might be looking at a lot more print businesses that won’t make it out the other side. It’s not going to be an easy spring and summer, but coming off such a good year as 2019 might just let us make it through this crisis.

Profits

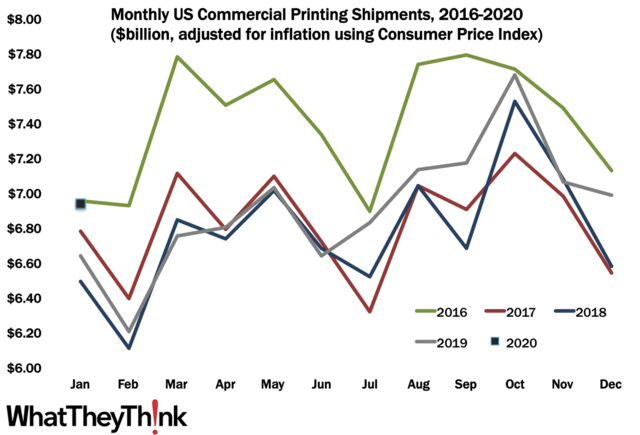

OK, so the most recent profits data is hardly a cute puppy pic—but then not all puppies are cute. (Don’t send letters.)

Annualized profits for Q4 2019 took a nosedive from $720 million to -$170 million. (See? We as an industry don’t need a major crisis to lose profitability.) Actually, this is just the latest chapter in our “Tale of Two Cities” narrative, this time with the profitability gap between large and small printers narrowing.

In Q2 2019, for large printers (those with more than $25 million in assets), profits before taxes were -6.66% of revenues. In Q4, this improved to -1.99% of revenues. So that was good. But for small printers, profits before taxes in Q3 were 8.49% of revenues. In Q4, this dropped to 3.15% of revenues. So that was bad. While large printers continue to drive down overall industry profitability, a decline in small printers’ profitability isn’t helping. For the industry on average, profits before taxes were -0.18% of revenues, and for the last six quarters, they’ve averaged 1.19% of revenues.

We won’t see Q1 2020 profits data until June and we won’t see the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on profits until we get Q2 profits data in September. If we’re all still here.